What ritual tools are required to practice Wicca? Theoretically, none at all—as the Witch’s will is the most important tool. But Wiccans, it may be said, rarely travel light. This article looks at the traditional altar tools that are used in the Gardnerian tradition of Wicca.

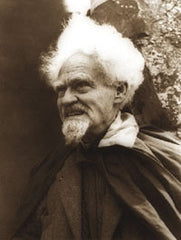

Gardner's legacy

Gerald Gardner, who first described and named the Wiccan religion, prescribed a list of tools for the Witch. His books and papers talk at length about the acquisition and use of ritual objects. Gardner was influenced in his thinking by Aleister Crowley, English Freemasonry, Solomonic magick, the new field of cultural anthropology, and various myths about European witchcraft.

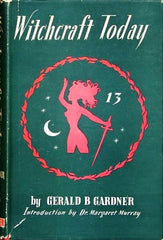

Though the information in Gardner’s writings is spotty and often contradictory, it has been hugely influential. Many of the Gardnerian tools are found on the altars of both Wiccan and non-Wiccan practitioners. Others, like the scourge and cords, have largely fallen out of use, except in the strictest traditional covens. The descriptions of the tools come from Gardner’s 1954 book Witchcraft Today, and the collection of papers known as the Gardnerian Book of Shadows.

So what are the “true” tools of the Witch? It depend on who you ask. Even within Gardnerian witchcraft, the number, order, and use of the tools varies. But first, a list of the tools of old-school Wicca:

Sword

The Sword is a long knife. It symbolizes power and authority. The sword entered the Craft as a legacy of Western ceremonial magick, where the magician wields a consecrated sword as an implied threat to unruly spirits. The magick sword was traditionally made of the finest smithwork possible, and engraved with Hebrew prayers or magickal glyphs.

Wiccans use the sword to cast a circle. It may also be a symbol of rank within the coven. Gardner says that a chief priestess may wear a sword on her belt when standing in for a priest. (But that no tool enables a priest to stand in for a priestess.)

While the sword is often listed first among the magickal tools, many Witches, including Gardner, say that the sword is not really necessary if you have an athame. Because of the size and cost of a ritual sword, it is common for a coven of Witches to share a single sword.

Athame

The athame is a small (relative to the sword, anyway) knife with a variety of ritual uses. Gardnerian Wiccans prefer a black-handled knife with magickal symbols inscribed on the handle. It is usually double-edged. Both the word “athame” and the black-handle requirement come from the Key of Solomon, a medieval grimoire which was studied by Gardner.

In Wicca, the athame stands for the element of Fire. It is used to cast the circle, charge objects with energy, and to represent the God in a symbolic Great Rite. It is never used for violence. If an athame draws blood, in most traditions, it must be either ritually cleansed or destroyed. Most Witches use the athame purely for magickal/energetic work, and have a separate knife for cutting objects.

Boline

This is the “White Handled Knife” described by Gardner. Sometimes it has a curved blade. Basically, the boline performs cutting tasks on the physical plane, while the athame works on the spiritual/astral planes.

Witches use the boline for magickal-mundane work, including harvesting herbs, cutting cords or parchment, and inscribing ritual candles. Boline is alternately spelled bolline, boleen, or bouline. It is an archaic word related to burin, a carving chisel.

Wand

The wand is the elemental tool of Air (or Fire, in Golden Dawn influenced trads). For Gardner, it is related to the staff of Mercury used to escort souls to the afterlife, and the thyrsus, the pinecone-tipped rod of Dionysus. Witches’ wands are usually made of wood—especially from a tree with magickal significance. It may be personalized by carving or painting. Gardner names few requirements for the magickal wand, except that it be phallic in shape.

Witches use the wand as an elemental tool, for directing energy, and sometimes for casting the circle. The wand is sometimes substituted for the sword or athame by those who object to the violence implied by the blade. Gardner tells us that the wand is used for calling up spirits “to whom it would not be meet to use the sword or athame.” These beings may include Angels (who may be invited, but never commanded) or Fae, who are known to dislike metal.

Pentacle

The pentacle is a round object bearing the five-pointed star, the primary sacred symbol of Wicca. It may also be called the disk, coin, paten, or platter. It represents Earth, and the life-giving properties of that element. In the Gardnerian material, the role of the pentacle is in summoning spirits, consecrating tools, and blessing offerings of food.

Perhaps mindful of Britain’s anti-witchcraft laws, Gardner suggests making a pentacle that can be easily concealed or destroyed if the Witch is discovered. He recommends a pentacle of wax, or else a platter with the magickal symbols painted temporarily in ink. These days, of course, Wiccans may keep a more permanent altar pentacle. Wood, metal, and clay are appropriate materials for the pentacle or Earth disk.

Censer

The censer (and incense) are used to prepare the ritual space. Ritual censing banishes evil, and makes the circle more inviting to spirits and deities of the desired kind.

Wicca came about before the invention of quick-lighting incense. Early British covens would have preferred a traditional swinging censer with a lid, along with resin incenses. But Gardner states that the censer can be replaced, if necessary, with sweet-smelling herbs and a dish of coals.

Cords

The Witch’s cord, or cingulum, is a length of rope that may be worn as a belt. In Wicca, the cords are often given to the new initiate and worn at each subsequent ritual. Along with the athame and the censer, Gardner lists the cords as one of the three tools that must always be present in the Witch’s circle.

The cords are generally braided by hand from natural fibers. The traditional length of the cords is nine feet (three times three, an important number in Wicca.) In some traditions, the color of the cord signifies the Witch’s rank within the coven.

Besides keeping the Witch’s robes in place, the cords have various other uses within Wicca. A nine-foot cord, folded in half, is used to measure out the radius of the nine-foot circle. Knot magick—tying and untying knots to release energy—is another ritual function of the cords.

But let’s get down to brass tacks: Gardner, like many a proper British gentleman, was obviously a little bit into BDSM. The Gardnerian Book of Shadows is full of rituals that involve tying up initiates in circle. The mild, schoolboyish kink of his Wiccan rites is another use of the cords. He also hints that the cords can be used in blood and breath control—a spiritual/erotic practice that can be extremely dangerous when undertaken by beginners.

Obviously, tying up aspirants is not the kind of thing that goes on in public rituals and fluffy-bunny Wiccan covens. Wiccans face enough PR trouble without innuendos of hazing. The Wiccan covens I know who use cords use them for mainly ceremonial dress. The cords are presented to the initiate with each new degree. Over time, they become kind of a souvenir belt, dangling with various tokens of the Witch’s experience and offices within the coven.

Scourge

Ah, the scourge. The ceremonial whip is another of Gardner’s ritual tools that’s sometimes embarrassing to modern Wiccans. The scourge or flail is an age-old symbol of power and domination. In Gardnerian ritual, it represents the pain that everyone must endure in life. It stands in contrast to the kiss, which symbolizes pleasure and the gifts of life.

Maybe Gardner was inspired by the ritual flagellation in mystical branches of the world’s great religions. Or maybe he just wanted an excuse to be tied up and whipped. We’ll probably never know. In any case, the scourge has eight tails with five knots in each tail. It is usually made of leather or rope. The scourge is not used to draw blood, but only for light flogging to raise energy in circle and to purify the aspirant. The scourge is the last item in the canonical list of Gardnerian tools.

Chalice

The chalice symbolizes the eternal womb and the generative power of the Goddess. On the Wiccan altar, it is used to hold beverage offerings. (Traditionally wine, but also water, milk, mead, or ale.) The chalice stands for the female principle in the symbolic enactment of the Great Rite. To Gardner, it is related to the Holy Grail of the Knights Templar, a mystic cup with boundless power to heal and restore.

A core Wiccan ritual involves the High Priest and High Priestess sharing a drink from the chalice, which may also be passed around the circle. A silver chalice is traditional, one large enough to hold the beverage offering.

Cauldron

In the Gardner materials, the words “cauldron” and “chalice” are often used interchangeably. (The cauldron being a Celtic-inflected version of the womb of the Goddess.) Yet many witches keep a ritual cauldron separate from the chalice or cup, and use it in subtlely different ways.

The main advantage of the cauldron is that it can carry heat. It is a dark, warm vessel where alchemical transformations can take place. The cauldron may be used to burn incense, to prepare potions and brews, or to ritually mix spell ingredients. The cauldron can also hold food or drink offerings, or water for scrying.

Besom

A Witch’s broom is called a besom. It is made from a bundle of twigs or straw tied to a handle. In Wicca, the besom is used to purify the circle by sweeping away negativity. It also plays a part in the handfasting ritual of “jumping the broom.”

Bell

The bell is primarily used in Wiccan rituals to focus the participants’ attention. The Gardnerian Book of Shadows prescribes a certain number of knells of the bell for each different ritual. Solitary Wiccans may keep a bell for energetic clearing, meditation, or invoking the Goddess.

Necklace

The necklace is not among the core tools of Wicca, but Gardner mentions it on several occasions as a requirement for the female Witch: “At witch meetings every woman must wear one.” There are many tales of necklaces in world mythology, and depictions of Goddesses who are nude except for a necklace. The circular shape of the necklace is thought to symbolize the eternal cycle of rebirth. The necklace may be decorated with talismans or symbols of rank. But, the material and design of the necklace are unimportant, “as long as it is fairly conspicuous” (Gardner, Witchcraft Today).

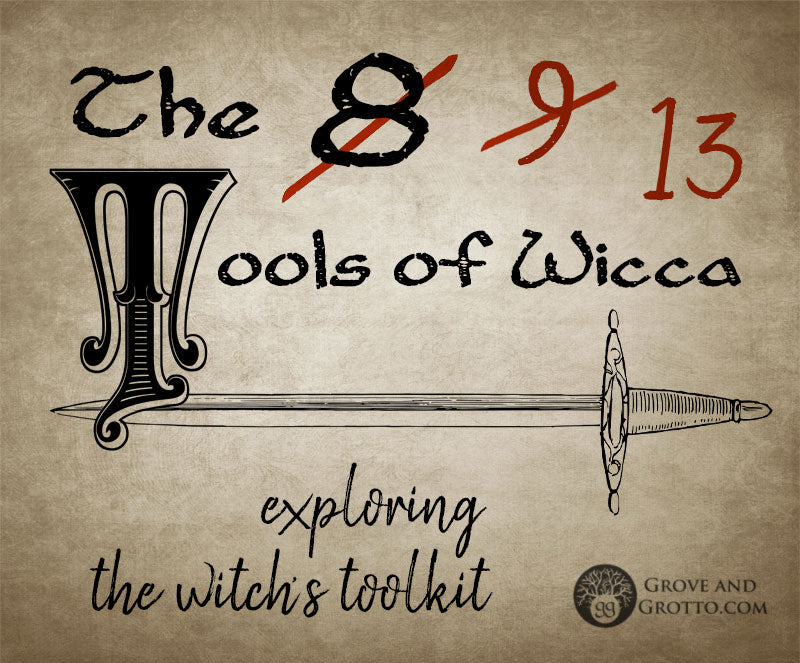

So how many tools are in Gardnerian Wicca, again?

According to the “Father of Wicca” himself, there are eight. They are, in order: The sword, athame, boline, wand, pentacle, censer, cords, and scourge. Gardner was almost certainly influenced by Freemasonry, which also has eight tools. Eight was an important number to the Knights Templar, the mystical Christian order which has trickled down into Western esotericism.

But wait! Not all of the tools on Gardner’s list are easy to come by. The poor witch may have to improvise with things found around the house, or do without. Gardner tells us that only three of the Wiccan tools are really essential for ritual: The athame, the censer, and the cords. These three, “and one or two other tools are quite enough to work with.” The other five are used only occasionally.

More troubles with the eight: The sword is often conflated with the athame. Why have both if they’re basically the same? Then there’s the whole issue of the vanishing pentacle. (Now it’s a pentacle, now it’s a biscuit tray. Move along, Inquisition—there’s nothing to see here.) Gardner never really explains how a Witch can have a set of ritually consecrated tools and regularly grab stand-ins from the kitchen or hearthside.

A handful of Gardnerian tools—the wand, pentacle, and sword/athame—are recognizable as three of the “elemental weapons” of the Golden Dawn traditions. But there is a conspicuous absence: We have three different knives (and a wand and a scourge), but no chalice, the elemental tool of Water.

So where is the chalice in Gardner’s list? Gardner claims his source was a secret cabal of hereditary Witches, and that he doesn’t know why the chalice was omitted. Perhaps it is a holdover from the Burning Times, when Witches were afraid to have a cup lest they be accused of parodying the Eucharist. (Goddess knows how they drank their daily ale.) Gardnerian rituals make extensive use of the chalice, but it doesn’t make the list.

Wiccan groups deal with the omission in different ways. The Alexandrian tradition (which is similar to Gardnerian), solves the problem by substituting the chalice for the censer in their list of eight. Alexandrians burn just as much incense as anyone, of course. But the poor censer is demoted to the rank of “altar dressing.” One Gardnerian coven I know just adds the cauldron/chalice to Gardner’s list—bringing the total number of tools up to nine. (An elegant solution, I believe, since nine is a sacred number in Wicca.)

What about the outer circle of tools: the besom, bell, and necklace? Though these show up repeatedly in Gardnerian rituals, they are not “officially” tools of the Witch, and are not presented to the initiate as such. Instead, they are objects that Witches use in ritual. We also don’t count the Book of Shadows, which is not a tool of ritual, but a tool used in preparation for ritual. Okay. I’m as stumped as you are.

In conclusion, there are eight, or nine, or thirteen tools (and tool-adjacent objects) in Gardnerian Wicca. Unless you are a male Witch. Then you don’t get a necklace, so there are twelve at most. And if you are setting up at Pagan Pride Day, best to cross the scourge off the list. And probably the sword. Maybe count the tablecloth and iPhone speakers, instead?

I’m not trying to make fun of Gardnerians here. (Except for one or two—you know who you are.) It’s just an example of the way traditions evolve and change over time. You’re no less a “real Witch” if you’re allergic to incense, or think ritual flogging is kind of silly. Whatever path you follow, build a collection of tools that resonate with what you feel is magickal.

Read more articles in the archive!